Installed on the northern wall of the Monash University student centre (Melbourne) is a curious geometrical object. If you don’t pay close attention, you might think it’s just a decorative sculpture. But it is actually a functional sundial — conceived and constructed by the mathematician Carl Moppert in the 80’s. This design appears to be unique. I browsed through many photos on Instagram tagged with #sundial, and I couldn’t find another one that looks quite like it.

Left: Photo taken on the winter solstice (June 22, 2017). Right: Photo taken on the summer solstice (December 21, 2016). The wall approximately faces north. The right hand side of the photo points westward.

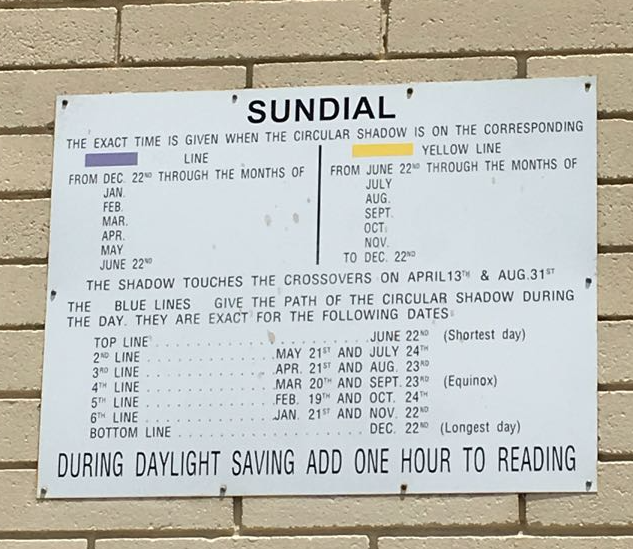

How to read this sundial? The university very helpfully posted instructions. What it says is that in summer and autumn (Dec 22nd to Jun 22nd; remember that this is the southern hemisphere), the hours are indicated by the purple lines, whereas in winter and spring (June 22nd to Dec 22nd), the hours are indicated by the yellow lines. Read the yellow lines for half of the year; read the purple lines for the other half. Got it. That’s easy enough. But why do we have to pay attention to the date when reading the sundial, and what are those 8 figures?

Left: The position of the sun (indicated by a red dot) in the sky throughout the year. The red line is the trajectory of the sun on the summer solstice. The blue line is the trajectory of the sun on the winter solstice. The figure 8 indicated by yellow and purple are the positions of the sun at 11:00am at different time points. It’s called an analemma. Right: The shadow of the gnomon on the sundial is represented by the red dot. The figure 8’s are analemmas corresponding to different hours. For example, the 11:00am analemma is the second one from the right. From right to left, the analemmas are for 10:00am, 11:00am, 12:00am, 1:00pm, 2:00pm, 3:00pm, and 4:00pm.

The animation above illustrates the movement of the sun in the sky throughout the year. The panel on the left shows that (unsurprisingly) the sun rises everyday from the east in the morning, and sets in the west in the evening. In addition, it also shows that the trajectory varies throughout the year. The summer solstice, for example, is the longest day of the year. The sun is high above the sky (as indicated by the red line). As the year progresses towards winter, the sun gets lower and lower everyday until it reaches its lowest trajectory on the winter solstice (the blue line). After the winter solstice, the movement is reversed: the day gets longer, and the trajectory of the sun becomes higher and higher every day throughout spring and early summer.

Imagine that every morning at 11:00am, the sun leaves a mark in the sky. After 365 days, those marks form a giant 8-figure in the sky. In the animation, I use purple dots for days between the summer solstice and the winter solstice (basically autumn and winter), and yellow dots for days in the spring and summer. This is because on two days in the year, the trajectories of the sun are identical, but the its positions on the trajectory are different for each hour. It was therefore necessary to use different colors to differentiate the two.

At this point, the design of the sundial should be obvious. It is simply a map of the positions of the sun throughout the year, projected on a vertical surface. The 8 figures represent the trajectories of the sun at different hours. If you are waiting for a friend for lunch at noon, you can use the sundial to tell if he or she is late, but remember to wait for the shadow to reach the purple line if it’s the autumn, and the yellow line if it’s spring.

So, the basic principle is this: since the position of the sun at a certain hour depends on the day of the year, and since the metal ring that casts the shadow on the wall (it’s called the gnomon in the lingo of sundial enthusiasts) does not change its position, two markers, the purple and the yellow lines in this case, are needed for each hour.

If that seems to be too complicated, it’s also possible to use single markers to indicate the hours, but the position of the gnomon would have to change according to the day of the year. This can be achieved by a computer-controlled mechanism that moves the gnomon on the wall, but there’s a low-tech solution: let the sundial user be his or her own gnomon. This type of sundial is called the analemmatic sundial. I found one in the Blackburn Lake Sanctuary — a park not too far away from the university. As you can see from the photos below, since you are the gnomon, you stand on the square corresponding to the month of the year, and the location of your shadow indicates the hour. No purple/yellow line is needed, because the difference in the locations of the sun is compensated by where you stand.

The analemmatic sundial at the Blackburn Lake Sanctuary. Left: To use the sundial, you stand on one of the squares. Right: your shadow is cast on a low circular wall. You can read the time directly from the numbers painted on the wall.