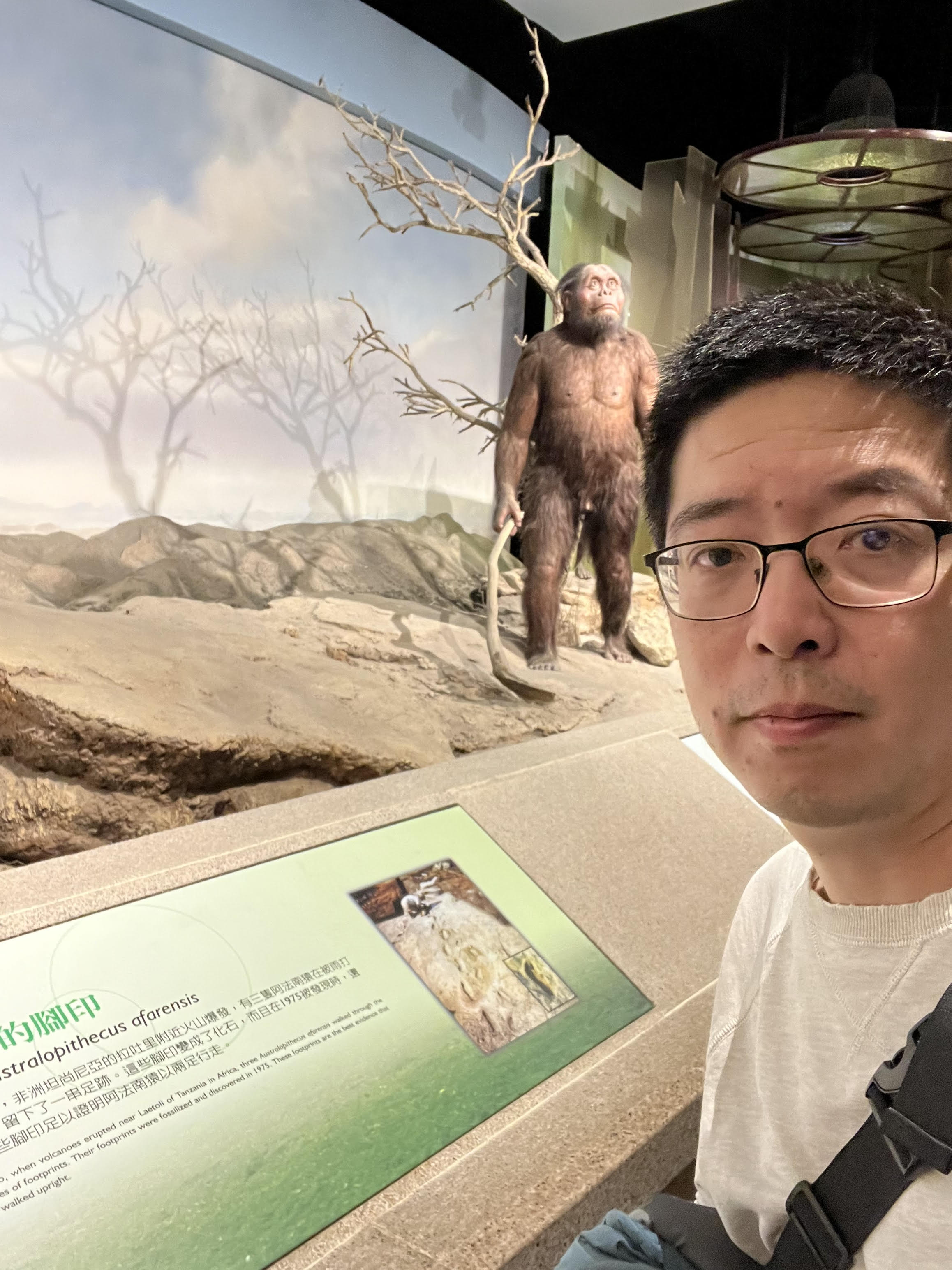

Today I visited the National Natural History Museum in Taichung, and I found the exact location where I was introduced to the music of the Beatles!

It was a school excursion when I was a boy. In the anthropological hall of the museum, there was a display of the site in Ethiopia where Donald Johanson discovered Australopithecus. Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds was playing because that’s the music Johanson was listening to while his team dug up Lucy. I actually paid no attention to any of these facts, because I was listening to the music. After that excursion, I bought Beatles albums one by one until I found Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.

I returned to the museum after decades living abroad, and I was very happy to have discovered that the museum has been playing Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds continuously all these years.

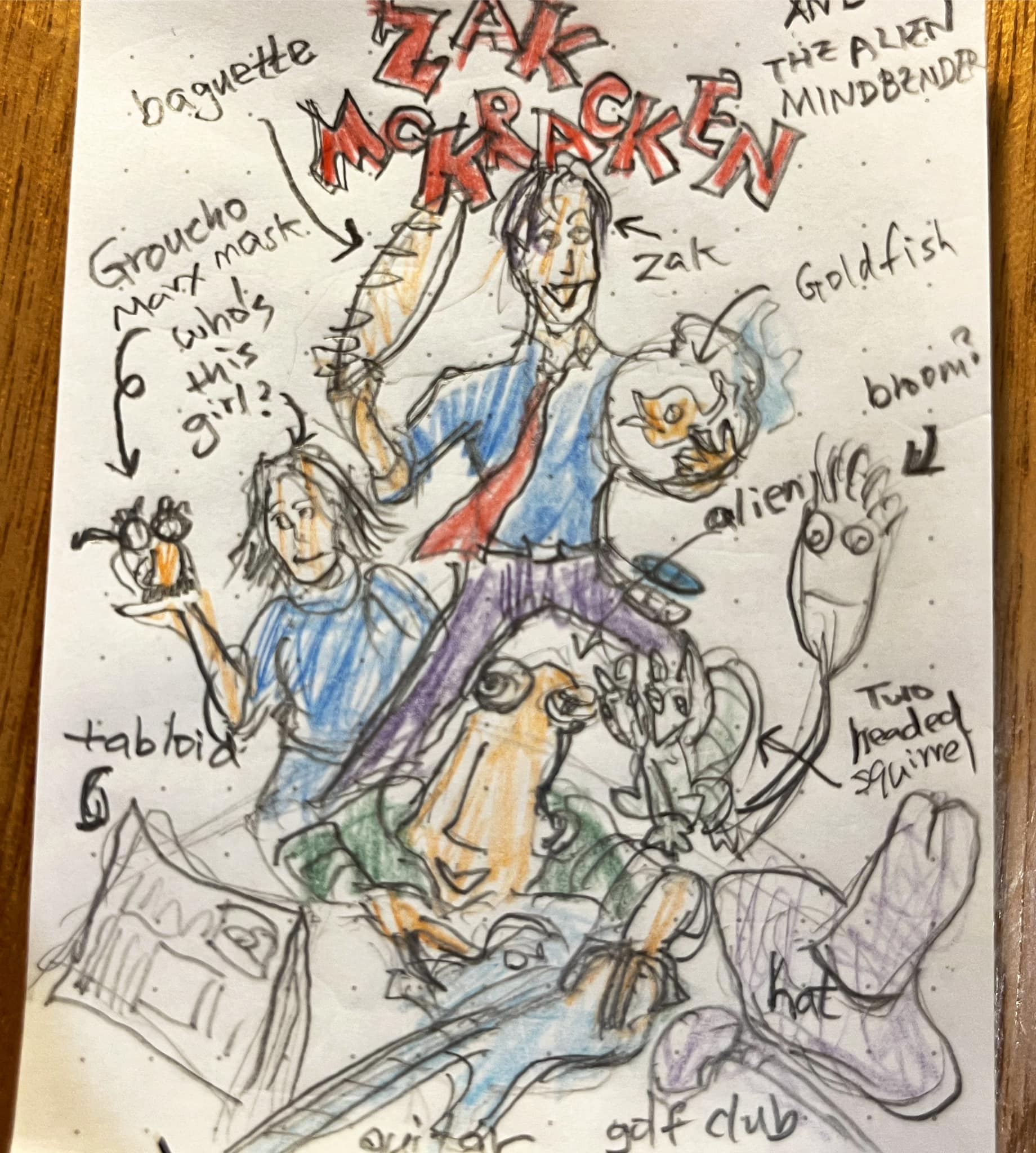

A tribute to Zak McKracken and the Alien Mindbenders, an old adventure game. The game has the greatest cover art ever. I haven’t played the game myself, but what could the plot be? Zak McKracken, a tabloid journalist is holding a baguette and a fishbowl, standing on a pile of fallen alien guitarists in cowboy hats. There is a broom with a face, a two-headed squirrel, and a girl holding a Groucho-Marx mask. Somebody should turn it into a children’s book.

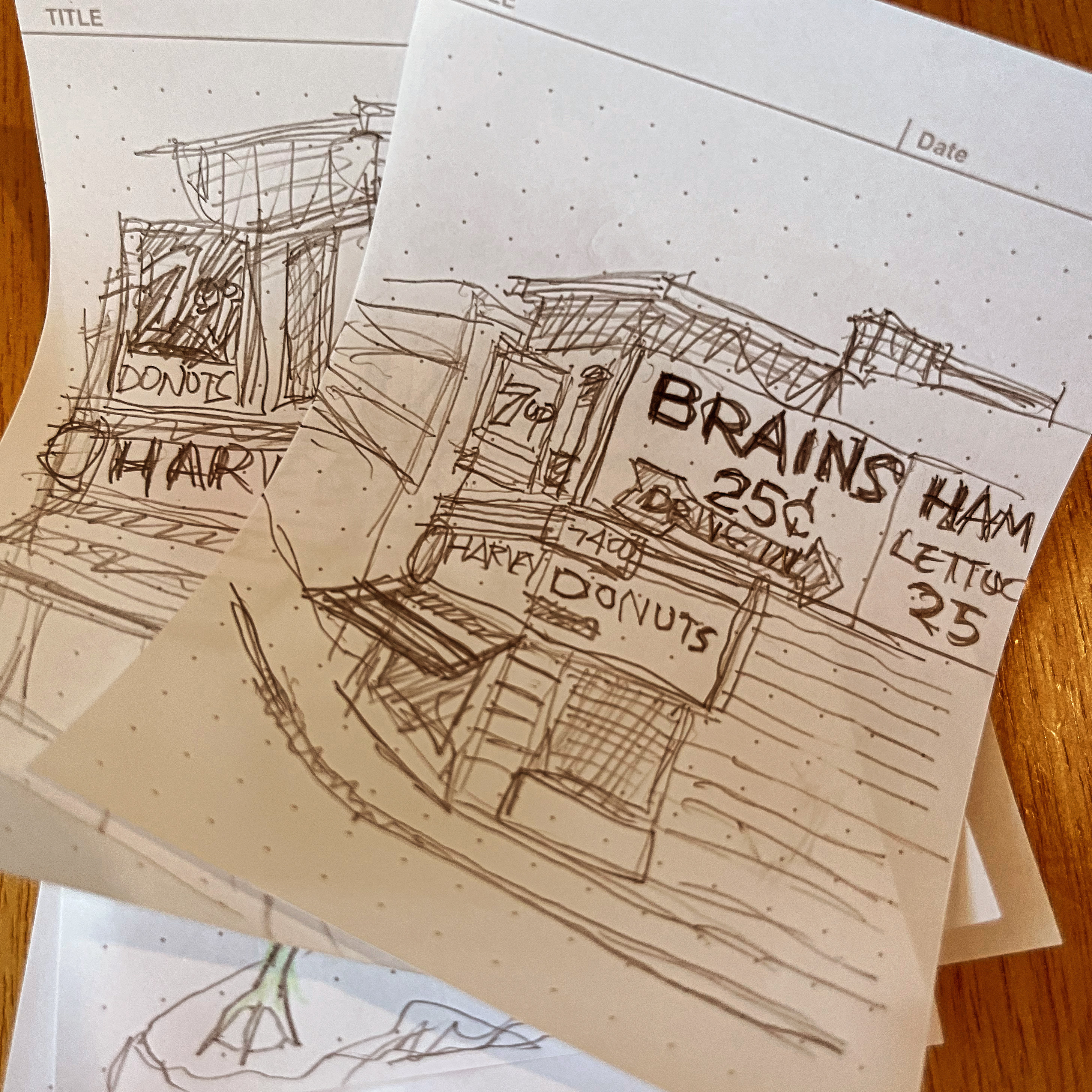

A friend shared with me a photo of a sign that says “Brains 25c Drive In”. It’s on the cover of the Bill Frisell album Where in the World? (1991), and many other places. It was a real sign advertising a fried brain sandwich, found in St. Louis, Misouri in the 70’s and 80’s.

Guitar learning diary: As I learn to play the guitar, I realised that I might be able to make musical associations without mental awareness. It’s probably because I am not familiar enough with the language of music to surface musical feelings to a conscious level. For example, yesterday, I tried to play some dominant 9 chords in a book. I was learning the fingering so I wasn’t attending to the sounds of the chords. It’s all mechanical at this stage. If you ask me to imagine a C9 chord, I wouldn’t be able to do it. I don’t know how to use a 9 chord in a musical context.

However, today, when I listened to the My Buffalo Girl track on Bill Frisell’s Good Dog, Happy Man album, I noticed that he played an interesting chord that sounded dissonant but musical at the same time. I looked it up in the Bill Frisell: An Anthology songbook, and what do you know? It’s a dominant 9 chord!

This happened to me before. I was interested in Miles Davis' So What, so I tried to play a couple of bars of Miles' solo. It was mostly an exercise to learn the Dorian mode. Then, for no apparent reason, I thought about Bill Frisell’s Monroe (again, from the Good Dog, Happy Man album) and tried to play it. It took me a while to discover that Monroe is in Dorian mode!

I am not sure if these are all coincidental, but I suspect that an interesting psychological phenomenon is in the play.

One of the zanier moments in Penn & Teller Fool Us: While Penn used a magic trick to comment on the New Testament (in which Teller was both the camel and the rich man at the same time), he said that heaven to him was listening to Sun Ra playing Bob Dylan tunes, while eating vegan fudge and watching the Tree Stooges chasing a honey badger on TV.

I’ve been reading two books about hacking. Interestingly, both books make references to the novel The Crying of Lot 49 by Thomas Pynchon. The first book is Exploding the Phone: The Untold Story of the Teenagers and Outlaws Who Hacked Ma Bell by Phil Lapsley. In an interview of Ron Rosenbaum, whose article Secrets of the Little Blue Box (published in Esquire Magazine in 1971) brought phone phreaking into the awareness of the public, Rosenbaum said that his vision of the phone phreaks of the 60’s and the 70’s was influenced by the underground communication networks described in the novel.

When I started to read the book, I didn’t associate phone phreaking with Pynchon. But of course, Pynchon loves secret communication. The second chapter of Lapsley’s book on the birth of Bell System and AT&T, he cited optical telegraphs of the 18th century as an early form of long-distance communication network. Incidentally, optical telegraphy is one of the main themes of Pynchon’s novel Mason & Dixon.

The second book I am reading is the The Cuckoo’s Egg by Cliff Stoll. It’s a classic non-fictional account of Stoll’s experience of tracing the footsteps of German hackers through the mazes of Internet and government agencies in the 80’s. Although he didn’t explicitly mention Pynchon, in Chapter 29, he gave a technology company the name Yoyodyne - the name of a giant defense contractor in The Crying of Lot 49.

It’s very interesting to me that Thomas Pynchon (rather than, say, William Gibson) is the author that people turn to when they talk about hackers and phone phreaks.

PS: I am now reading The Hacker Crackdown by Bruce Sterling. Guess what? It also makes a reference to Thomas Pynchon!

I had a surreal experience reading Steve Jobs and the NeXT Big Thing by Randall Stross, published in 1993 (I found a copy for free). Stross argued convincingly that NeXT was hopeless. Had I read it in 1993, I would have thought that the analysis was spot on. Who would have thought that in 2023, people would be still using essentially NEXTSTEP? Also, the entire workstation market has been wiped out, but IBM is still selling mainframes!

My family has been watching the Penn & Teller: Fool Us TV series. I was reminded of a 2008 paper published in Nature Review Neuroscience about the psychological aspects of magic. Teller was listed as a co-author (among several well-known magicians). There is a very remarkable sentence in the paper: “One of the authors of this Perspective (referring to Apollo Robbins) is a professional thief.”