A recent paper shows that our vision is so sensitive to light that human subjects can detect the presence of one single photon shot into their retinas. While scientists have been trying to establish the lower limit of visual sensitivity for a very long time, and it is generally accepted that a small number of photons are sufficient for detection since the 40’s, new advances in quantum optics finally allow us to manipulate light at single photon precision, and it is the first time that direct evidence for single photon sensitivity is demonstrated in a psychological experiment.

While I am very excited about this research, I found it difficult to get students to be excited about it. This probably has something to do with the fact that we very rarely talk about light in terms of photons. We are very comfortable with psychological terms such as “brightness”, but relating the experience to the physical composition of light, especially at the level of fundamental particles, is far from being intuitive. I have therefore made some ballpark calculations, to get a sense of the numbers of photons available in the environment, using numbers that can be looked up without consulting specialised journals. In sum, these calculations show that while modern light sources generate astronomically large number of photons, very dim objects, such as stars in the night sky, project surprisingly few photons into our eyes. The fact that we can see very dim stars already suggests that human vision must be sensitive enough to detect small numbers of photons.

In the followings, I will explain the steps in a self-contained way, but please refer to the excellent textbook by Rodieck[2] for details. It is important to note that the word “brightness” that we use in our everyday conversation is not very precise. It does not correspond to a single physical or psychological quantity. Instead, depending on the context, it can refer to different concepts. This article also serves as a summary of some of the technical terms that are useful for quantifying “brightness”.

Photons emitted by a light bulb into the room (watt)

Every light source emits photons of a range of wavelengths. To estimate the number of photons, it is important to know the distribution. The spectral power distribution of an incandescent light bulb can be approximated by black-body radiation, which is described by Planck’s law:

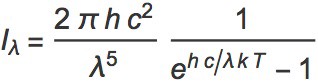

There are three constants in the formula: h is Planck’s constant (6.6210^-34 Js), c is the speed of light (299792458 m/s), and k is Boltzmann’s constant (1.3*10^-23 J/K). Setting the temperature T of the filament to 2800K (a typical value for a household light bulb with a warm white light), the power distribution is plotted in Figure 1. Note that the wavelength (λ) of photons in the formula is in the unit of meters, but I have converted them into nanometers (nm) in Figure 1.

Figure 1: The spectral power distribution of a 2800K light bulb. The shaded region is the visible spectrum.

Take a green photon (wavelength = 555 nm) for example, the figure shows that for each cubic meters of the filament, about one third of a trillion (3.810¹¹) joules (J) of energy is produced every second. In other words, 3.810¹¹ watts (W). The figure also shows that most of the energy (~90%) produced by the light bulb is outside the range that is visible to the human eye (390–700nm, indicated by the shaded region in the figure).

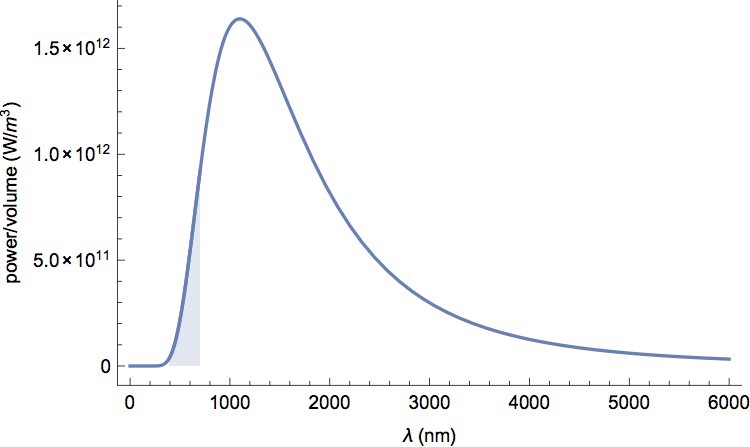

This figure is not very useful for our purpose, because I don’t know the volume of the black-body radiator that is equivalent to the filament. However, since I know that the typical power of a 2800K light bulb is 60W, I can normalise the figure so that the area sums to 60W. The new distribution is plotted in Figure 2. Now we know that a 60W, 2800K light bulb produces 0.0085W (or 0.0085 J/s) of green photons.

Figure 2: The curve shown in Figure 1 is normalised so that the area of the curve is 60W.

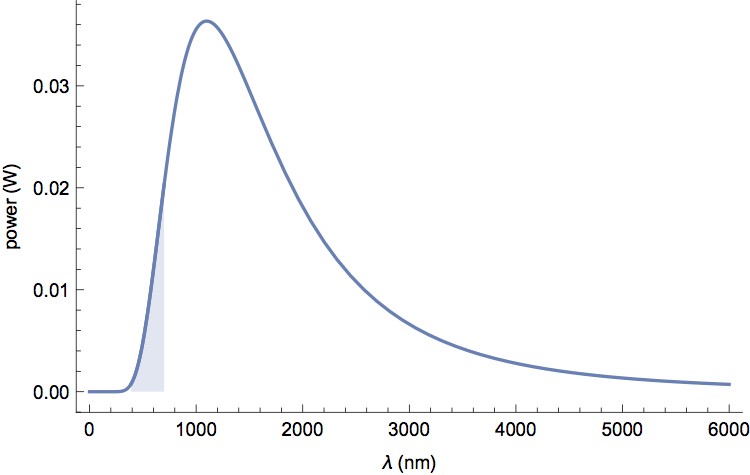

Since the energy of a photon of wavelength λ is hc/λ (unit is in joule, if λ is in meters), it’s straightforward to calculate the radiant flux (the number of photons produced per second) of the light bulb. The numbers are plotted in Figure 3. Summing the area under the curve, we conclude that the light bulb emits 8.210¹⁸ photons every second in the visible spectrum.

Figure 3: The radiant flux (the number of photons produced per second) of a 2800K, 60W light bulb is indicated by the shaded area. Only the visible spectrum is plotted. The dashed curve is the luminous efficiency function.

From physics to psychophysics (lumen and candela)

Wattage is a unit for measuring power (that is, the amount of energy that is used to power the device per second). It is not a very good measurement for quantifying light sources because it is dependent on how the photons are generated. Black-body radiation is not a very efficient method for illuminating the room because most of the energy (~90%) is converted into heat. There are much more efficient ways for generating light in the visible spectrum. For example, LED lamps, which have become common in the last decade, operate at much lower wattages (typically just a few watts), but they can be as bright as incandescent light bulbs.

What we need is a quantity for describing how bright the lamp is, in a way that is not dependent on how electrical energy is converted into photons. To achieve this end, most manufactures specify the brightness of lamps in the unit of lumens. The principle is very similar to what we have discussed above, except that in lumens, the energy produced is expressed not in terms of quantities defined in physics, but in quantities that are relative to psychological measures. It is a more useful unit for deciding which light bulb to buy, because our sense of brightness is not just about the energy carried by the photons. Photoreceptors in the retina are not like steam engines. Activating them is not like heating up a cup of water or cooking an egg. Instead, energy has to be carried by photons of certain wavelengths to be effective. For example, although a blue photon carries more energy than a green photon, we are more sensitive to the less energetic green photon. The sensitivity is measured as the luminous efficiency function (dashed curve in Figure 3) in psychological experiments (the numbers are available for download in here). From the curve, we see that the large number of photons at the rightmost side of Figure 3 do not contribute much to our perception of brightness, because the photoreceptors are insensitive to them. Energy in that range of the spectrum is “wasted”.

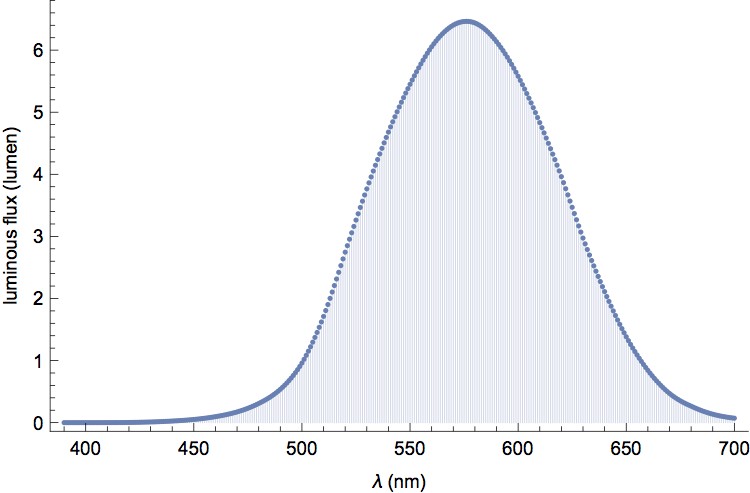

In order to express the brightness of a light source, it therefore makes more sense to weight the radiant flux shown in Figure 3 according to to luminous efficiency function. The weighted radiant flux is known as luminous flux, measured in lumens. At the peak of the luminous efficiency function (555 nm), 1 lumen is 4.09*10¹⁵ photons/s. For other wavelengths, the calculation is weighted by the luminous efficiency function (Figure 4). Summing the luminous flux of all wavelength in the visible spectrum, we get 691 lumens for our 60W, 2800K light bulb.

Figure 4: The luminous flux of our idealised light bulb.

Another quantity that is sometimes used to specify the brightness of light bulbs is candela (cd), which corresponds to the brightness of typical candles used in the olden days. I haven’t seen this unit used in consumer products, but my parents said that they used to shop light bulbs by the candela. We divide the 691 lumens by 4π, and get 54.2 cd. Our light bulb is therefore apparently 54 times brighter than a “standard candle”. 4π is in the unit of steradian (sr), and it is the “solid angle” of a sphere. By dividing the 691 lumens by 4π sr, we are assuming that equal numbers of photons are emitted by the light bulb, in all directions in space. Unlike light bulbs, some light sources are much more concentrated, casting strong beams of light at particular directions. The candela is a more suitable measure for such light sources. It is said to be a measure of luminous intensity.

Summary: By looking up two pieces of information that are readily available (the color temperature and the power) for consumer-grade incandescent light bulbs, it is possible to estimate the radiant flux — the number of photons that are emitted into the environment every second. Most manufacturers also specify their products in lumens, which is a measure of luminous flux. It is also possible to estimate the radiant flux from lumens.

The brightness of a computer monitor (luminance)

Our theoretical light bulb produces 8.2*10¹⁸ photons in the visible spectrum every second. These photons are dispersed into the room, which are bounced around or absorbed. Only a fraction of them enter the eye. To estimate that number, the radiant flux and the luminous flux that we have worked with before do not provide enough information about geometrical relationship between the light source and the eye. A different kind of measurement is needed.

The flat surface of the computer monitor has a simple geometry, making it the perfect starting point for this type of calculation. The brightness of computer monitors is often measured in luminance, which has the unit of lumen/m²/sr. The unit is also written as cd/m², because (as we have seen before) a candela (cd) is lumen/sr. For desktop computers, 150 cd/m² is a typical value. Let’s see if we can work out the number of photons from this piece of information.

The procedure is very similar to what we have done before with the black body radiation. We begin with the spectral radiance of the monitor, which specifies the power of photon production at every wavelength, for each square meters of the monitor, and for each steradian at the direction pointing to the eye. The concept is similar to the power function illustrated in Figure 2, except that the scale is expressed in a unit that is normalised with respect to the size of the monitor, and the solid angle pointing to the eye.

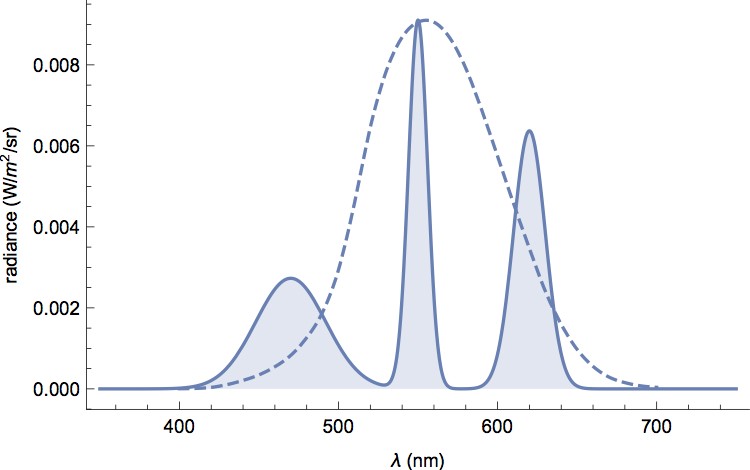

Figure 5: The spectral radiance of an idealised computer monitor, displaying a uniform white pattern. The dashed curve is the luminous efficiency function.

Figure 5 illustrates the spectral radiance function of a hypothetical monitor, which should be realistic enough for a typical 150 cd/m² LCD monitor. I used the summation of three Gaussian distributions to approximate the spectral power distribution of LCD monitors, which can be found in many websites. The tricky bit is that this type of figures are usually plotted in arbitrary scale in the y-axis, whereas a physical scale that matches to the luminance of the monitor is needed for our calculation. With some trials and errors, I normalised the curve so that it peaks at 0.0091 W/m²/sr. Let’s check if this distribution produces 150 cd/m² luminance.

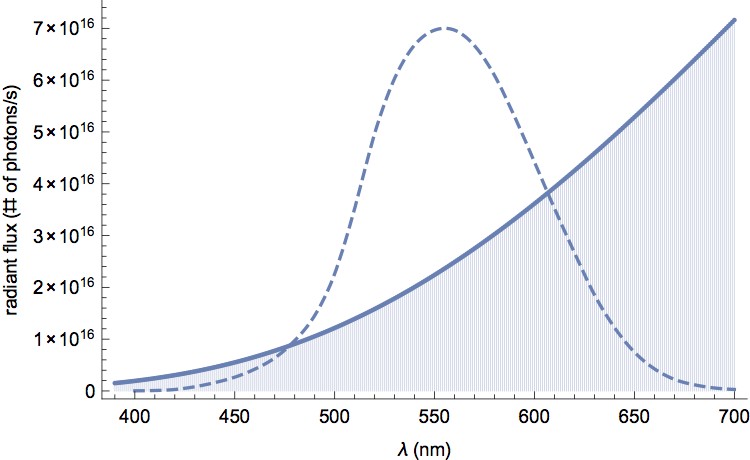

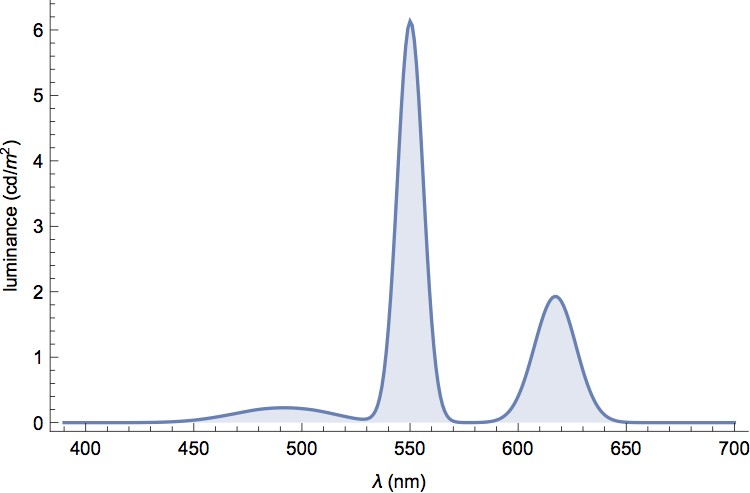

As before, we first express radiance in terms of the number of photons produced (Figure 6). Then, we weight the radiance with the luminous efficiency function, and then convert photon/s to lumen (as we did in Figure 4). The result is shown in Figure 7 — the luminance of the monitor as a function of wavelength.

Figure 6: The same as Figure 5, except that it is re-scaled to show radiance in the unit of photons/s/m^2/sr.

Calculating the area under the curve shown in Figure 7, we conclude that the total luminance is indeed ~150 cd/m².

Figure 7: The luminance distribution of our hypothetical 150 cd/m^2 monitor.

Photons in the eye

Calculating the area under the spectral radiance function in Figure 6 yields the total radiance of the monitor: 1.2*10¹⁸ photons/s/m²/sr. We are now ready to tackle the eye. Consider a situation where you are starting at a single letter, in 12pt font size, on the monitor, at 40 cm reading distance. What is the radiant flux, or the number of photons that enter the eye? Since total radiance has the unit of photons/s/m²/sr, we need two additional values: the physical size of the letter on the monitor (in m^2), and the solid angle of the rays enter the eye. The first value is easy: the dimension of a letter in 12pt font is about 4.2mm by 4.2mm. The area is therefore 0.00001764 m².

To calculate the solid angle, we need the size of the pupil, which changes with luminance. The diameter (in mm) of the pupil [1] is approximately 4.9–3*tanh(0.4 logL), where L is luminance in cd/m². Since we are staring at a 150 cd/m² monitor, the diameter of the pupil is 2.0 mm. The photons traveling from the centre of the letter to the pupil form a cone, 40 cm in hight and 2.0 mm in base diameter. With a little calculations, the solid angle of this cone is 0.00002 sr.

Finally, we multiple the area of the letter and the solid angle by the total radiance, and arrive at the radiant flux of 4.2710⁸ photons/s. About half a billion photons reach the cornea of the eye every second, of which about half are absorbed by the ocular medium. The radiant flux that reaches the retina is therefore **~210⁸ photons/s**.

Objects in the room

The luminance of objects in the room can be measured by a simple handheld device called the luminance meter. It operates like a camera. You point the lens to a location, adjust the focus, and press a button. The device gives you a luminance reading at a tiny spot surrounding the focus. I’m sitting in a well-lit office. The luminance of the screen of my iPhone, a piece of paper, and the surface of the desk is about 60~80 cd/m². The number of photons that reach the eye is therefore about half the number as our 150 cd/m² monitor. Dark corners in the room (still clearly visible) are about 5~20 cd/m². So, even in dark corners, a small surface area still projects about half a million photons to the eye every second.

It is raining outside, so the brightest object that I can measure is the lamp, which is ~2,600 cd/m². It is quite bright, compared to a clear blue sky , which is ~1,000 cd/m² [2].

Photons from the stars

The calculations above indicate that photons are abundant in our industrialised world. To get a sense of the lower limit of our visual system, it is educational to consider vision in naturally dark environments, such as star gazing. As indicated by an equation in Rodieck (1998), the total irradiance of a star above Earth’s atmosphere is 1.1510¹¹10^(-0.4M) photons/s/m², where M is the magnitude of the star. Polaris, one of the brighter stars in the night sky, has the magnitude of 1.98. The irradiance of Polaris is therefore 18565 photons/s/mm², but since only 22% of the photons are in visible range, the irradiance that is relevant to us is only 4084 photons/s/mm². After absorption and scattering in the atmosphere (~30%), we are left with 2859 photons/s/mm². Applying the size of the pupil in the dark (~40 mm²), the radiance flux of photons in the eye is ~10⁵ photons/s, of which about 57% are absorbed by the ocular media, so the radiance flux onto the retina is roughly only 50,000 photons/s.

If the retina collects photons like a bucket, it can accumulate as many photons as needed, and therefore should be able to detect very very faint stars. After all, it is how long exposure astrophotography works. However, the physiology of the eye and the retina imposes a “shutter time” of roughly 0.1 second on the operation of the photoreceptors. Within this shutter time, the retina only has about 5,000 photons to work with.

What happens if we are gazing at a very dim star? A star of 6.5 magnitude is normally barely visible to the human eye. Following the same calculation, only ~90 photons are available within the shutter time to excite the photoreceptors. According to Rodieck (1998, p141), in a condition where great care was taken to eliminate the diffuse light of the night sky, the dimmest visible star was determined to be 8.5 magnitude, which provides only ~14 photons to be detected by the photoreceptors. This observation alone suggests that photoreceptors are likely to be sensitive enough to detect a handful of photons.

Different senses of “brightness”

In this article, I have used the folksy term “brightness” in a few different senses. Let’s review:

Light bulbs are often specified according to their power consumption, in watts. It is not a measure of brightness, because the same unit is also used to describe engines, refrigerators, and so on.

Radiant flux (measured in photons/s) specifies the rate at which photons are poured into the room. It doesn’t tell you the rate at which photons get into the eye, because that depends on the geometry between the eye and the light source (When illuminated by the same lamp, a larger room feels dimmer, for example). It is therefore not really a measure of brightness.

Consumer products such as lamps and video projectors are very often specified in lumens, a luminous flux unit. It is similar to radiant flux, except that it is weighted by the luminous efficiency function. It is closer to the human perception to brightness than the radiant flux, but it is also not really a measurement of brightness (for the same reason as above). For consumer products, however, it is easy to understand and therefore is commonly used.

Candela, a measure of luminous intensity, is very similar to lumens, except that it is easier to use for light sources that are directional, such as search lights.

cd/m² is a measure of luminance. It specifies the rate at which photons are generated (weighted by human wavelength sensitivity) per unit area of the light source per solid angle at a certain direction. It is a local measure. The complex unit was designed so that the rate of photons that reach another surface (such as the eye) can be calculated. It is closest to our intuitive sense of “brightness”.

Without weighting by the luminous efficiency function, luminance becomes radiance.

Luminance and radiance are not very suitable for describing the brightness of stars, because they are too far away and essentially act like point lights. The solid angle that is needed for the calculation of luminance and radiance is not meaningful. Irradiance, in the unit of photons/s/m², is more appropriate for this case, because it specifies the rate at which photons hit a surface (such as the retina).

Notes

There are a few different approximations of pupil size. I arbitrarily picked one from Watson & Yellot (2012) A unified formula for light-adapted pupil size. Journal of Vision 12(10):12, 1–16.

Rodieck (1998) The First Steps in Seeing. Sinauer Associates, Inc. Chapter 6.